The Death and Rebirth of Subcultures

Pigeon post #03 - Subculture is dead and we killed it. What's next?

The idea of subculture is deeply entwined with youth counter-culture. The first that come to mind are modern popular aesthetic subcultures like Goth, Punks, or Hippies. The past century has seen many of them rise and fall all over the world. In its early years, the internet also facilitated the birth and spread of new ones. However, in the past few years, with new social media platforms and the rise of influencers and content creators, we’ve seen both the aesthetics and the people embodying them morph into something unrecognizable.

By definition, a subculture is a group of people that differentiate themselves from the dominant culture to which it belongs. They form a community around the fringes of what's popular, whether it be music, politics, fashion, or all of the above. Because of this, they thrive in societies with limited but accessible communication tech: good enough to have some mass media, but not with widespread corporate control.

Today it seems impossible to have an honest, all-encompassing subculture. Short form content, hyper-consumption, and the breakneck pace of trends have flattened once rich communities into fleeting aesthetics.

Subcultures didn't used to be something you could just buy into. Although often associated with unique styles, they weren't defined by them. Grunge was a largely music-based subculture. So was Punk. But they both strongly represented anti-fascist and socialist politics, rebellion, and activism. This is a defining feature of these communities and it is what educated their aesthetics. Punk abides by a DIY ethos because it is anti-capitalist, and because so many of its members are from the working class. When it first emerged, it was an anti-fashion fashion movement. So was goth, so was grunge, and so on.

However, over the years, with the success of Vivienne Westwood, with Marc Jacobs' infamous Perry Ellis 1993 show, the commercialisation of these aesthetics became an issue. As designers and brands commodified these aesthetics, they diluted their meanings until they became marketable trends, stripped of their radical roots. This has been the pattern for every subculture. First they emerge out of shared values, then they become somewhat popular, finally the fashion overlords take them over and market them to the masses. This is the classic rise and fall of a subculture. Even Westwood, who tried her entire career to retain her political edge, contributed despite herself to this pattern. Historically this cycle would only happen to a few popular movements over a few years, decades even. Exposure to them was limited, hence the long lifespan. This gave the community time to exist together meaningfully, before their ideas were appropriated by the masses. Punk is such an important part of history because the movement was allowed time to grow and leave its marks on society.

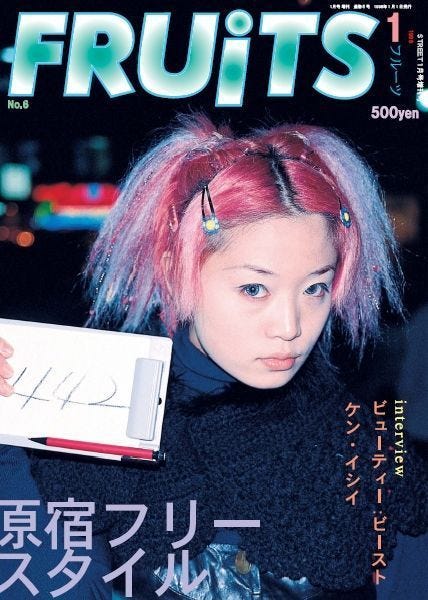

Unlike Punk, Harajuku fashion is a collection of style-based subcultures. Though not specifically political, the community is strongly defined by its celebration of individuality and self-expression. For this reason, it has always largely consisted of young radicals. Many credit its popularisation to the magazine FRUiTS which was hugely influential at the time, and still is. It was first published in 1997 by photographer Shoichi Aoki as a very simple platform; each page a full portrait of a uniquely stylish person alongside a brief profile of them and what they're wearing. This magazine singlehandedly popularised street-style photography.

Since its closure in 2017, the conversation around Harajuku has been pretty sad: the discourse has highlighted the thinning number of "cool kids" not only in Tokyo, but around the world. I'll never forget Aoki's quote in Dazed magazine stating “There are no more fashionable kids to photograph”. The Tokyo fashion scene, and Harajuku in particular, has been at the forefront of emerging fashion and fringe styles for decades. Seeing it wane has prompted questioning around what's happening to rebellious experimental people around the globe. Current street-style is much more performative than it used to be. People are acutely aware of their image. They know — and hope — that their outfits could end up in Vogue: Street style or go viral on Instagram through someone like @watchingnewyork. Everything is curated, built around self-promotion instead of sincerity. According to Aoki in his article for i-D: "Smartphones and social networks are partly to blame for our current slump. People can easily fulfill their desire for acknowledgement with a post online, and it doesn’t cost a thing. Fast fashion has also played a major role. It’s the very model of destructive innovation; while the average level of fashion has risen, it’s been almost entirely homogenized."

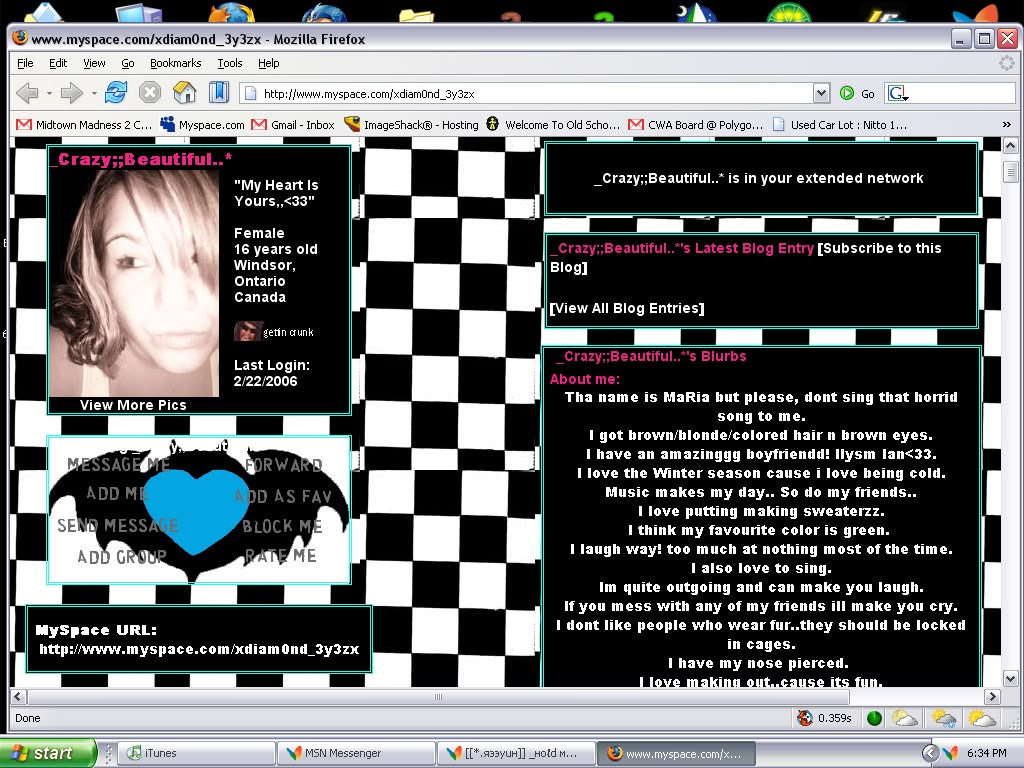

There was a moment in the early naughts, with the birth of forums and early social media platforms, when the internet actually aided in making connections. Websites like Tumblr made it easy for people to create community around a common interest, anonymously or not. Through these forums fandoms were born, an early internet mutation of the subculture. Fandom culture became a subculture in and of itself, albeit a peculiar one. These social networks weren't linked by values and aesthetics, they were almost exclusively focused on their common interest — sometimes to the point of obsession.

With the monetisation of social media, content creators are given financial incentive to push people into overconsumption. This has made it so that what you buy defines who you are. You're a fan of Taylor Swift? You must have the CD, the t-shirt, the poster, the earrings even... Did you go to the recent concert? I hope you bought a new outfit that clearly expresses which of her "eras" is your favourite! Even fandoms are now transactional. The depth of your devotion is only measured by how much you're willing, or able, to spend. No matter how much you truly love this music, you'll never be as big a fan as the person who owns all the limited edition vinyls.

Youth culture now is largely present on the internet, told through social media posts. If you spend time on Tiktok or Instagram reels, you've surely seen the term "-core" thrown around to define hyper-specific aesthetic identities. The suffix can be applied to any word to describe a trend or aesthetic associated with it. Less than a lifestyle, more than a trend, "-cores" are the acting replacement for subcultures. Watered down and easy to perform. It used to be that people who participated in subcultures on a superficial basis were labeled "posers" and rejected by the same communities they were emulating. Today everybody is a poser. You don't have to live on a ranch to be "cottagecore", simply owning a milkmaid dress will do it. What used to be a collective of like-minded people, sharing the same taste and values, is now just a group of people playing dress up. The thing is, the looks in subcultures used to function as a signal to other potentially similar people. If you were a goth and saw another goth-looking girl, you would know that you could be friends, or at least that you liked the same things and shared the same values. It was a social signal. Now you can go up to a person who looks like they're a part of your community, but you wouldn't know anything about them. For all you know, they could be a right-wing conservative. It feels like a betrayal to the community. The visual codes that used to signal likeness have been dulled and made it harder to find "your people".

The subcultures we knew are close to dead. As they take their last breaths I wonder what will happen to counter culture. Where will all that energy go? In the murmurs of conversations I've heard recently, a theme emerges. If the internet is where subcultures go to die, it feels natural to me that the only real subculture left is being off the internet.

The internet has never been so pervasive, omnipresent, infinite. Everyone and everything is in the cloud. Our devices have inserted themselves in every aspect of our lives. But it's also just become one giant ad. As soon as you log on, someone is selling you something. Or maybe it's you — your data, your attention — being sold. Corporations haven't just co-opted aesthetics, they've colonized our attention. People are sick of this, tired of the never ending cycle of consumption where nothing is ever enough. They want their attention back. They're talking about information overload, the impact on their mental health, how bad it is to have access to everything, and to be accessible, all the time. Some of my friends have been very explicit: telling me they're sick of the doomscroll, they want to be disconnected. They say they know that their phone is the problem. Some even say it's the root of all their problems.

It makes sense then that in corners of the internet I've seen the rise of dumbphones. Google searches for the low-tech alternative have been steadily on the rise. On YouTube, you'll see tutorials on how to "dumbify" your smartphone. I, myself, have "dumbified" my phone. Deleting all unnecessary apps and social media and making the interface borderline unappealing. There is an anti-internet, anti-smartphone movement on the rise. Funny how the community is forming on websites like reddit. It's true though, in varying degrees, people are trying to find their way out of this system. Some trying to live without a smartphone outright, others trying to find a middle ground. I've been trying to make the internet a place I visit, instead of carrying it with me everywhere. Trying as well to turn my devices back into tools, instead of vehicles for entertainment. "Dumb" tech does carry its own aesthetic, even as an anti-consumerist movement. It might still be vulnerable to commercial takeover. I can already see companies try to sell products made to "help us disconnect" — screen time managers, phone lock boxes and the like. Not having a smartphone can be tough, especially right now, when its usage is so entrenched in our everyday lives. However, as this movement grows, it could snowball. I can imagine in the near future, entire groups of people unplugged in phone free spaces. A new community of true renegades.

I would do anything to get off a smart phone. Seriously. And isn't it interesting we live in an era where everything is just culture. We're now in what I heard of as a social media recession. Everyone's over the engagement, and pushing (well hopefully) to go outside and I don't know - touch grass. Really fascinating read, and well researched!

loved reading every second of this, your writing is so intriguing and intricate 🧡🧡